There’s a quiet spell that falls when you step into a beautifully preserved historic home: the soaring ceilings, the intricate moldings, the craftsmanship that has outlived generations. Recent photo features celebrating “beautiful old houses” and century homes have gone viral again, as audiences crave elegance, authenticity, and tangible history in a largely digital life. Yet amid the admiration, one question rarely surfaces: what happens to your spine when you actually live, work, and move in spaces designed for completely different bodies, lifestyles, and daily demands?

Today’s renewed obsession with old-world charm—fanned by social media feeds full of high ceilings, narrow staircases, clawfoot tubs, and antique seating—has a quiet ergonomic cost. For anyone dealing with back pain, scoliosis, disc issues, or chronic neck tension, the romance of “timeless craftsmanship” can clash sharply with the physical realities of 2020s work and life. The result is an under-discussed tension: how do you preserve the soul of a historic space while unapologetically protecting your spine?

Below, we explore five refined, spine-conscious insights for those captivated by heritage homes and classic interiors—without surrendering their back health to nostalgia.

1. High Ceilings, Low Screens: Correcting the Vertical Mismatch

Historic homes often seduce with height—tall windows, generous cornices, chandeliers that float rather than hang. But the human eye and head now spend hours each day locked not on ceiling medallions, but on laptop screens, phones, and tablets that sit far too low in relation to this vertical drama.

In a room with 10–12 foot ceilings, the visual “center” of the space sits much higher than your actual working posture, quietly encouraging you to drop your head and round your shoulders to stay within your personal, lower visual field while your environment soars above. This contrast is subtle but real: people unconsciously accommodate grand vertical space by collapsing inward, especially during screen use. The result is a deeper, more sustained forward head posture and thoracic rounding—two key drivers of neck strain and upper back pain.

The refined correction is not to fight the architecture, but to recalibrate your vertical ergonomics. Raise monitors so the top third of the screen meets your eye level while you sit tall, even if that means repurposing stacked art books or custom wood risers that echo existing trim. In living rooms, avoid placing televisions excessively low beneath ornate mantels; instead, align viewing height with neutral neck posture, even if it means rethinking traditional fireplace-centered layouts. In a tall room, your spine becomes the quiet vertical reference line—design around it, not against it.

2. Antique Seating, Modern Spines: How to Sit with Grace, Not Guilt

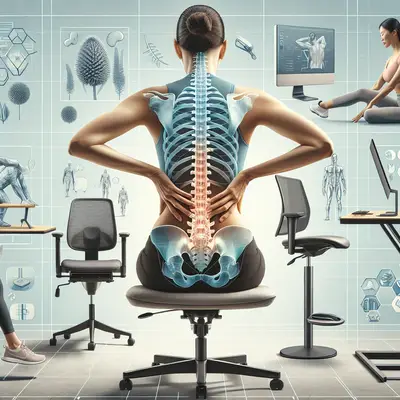

The current love affair with period furniture—slender side chairs, deep vintage sofas, carved parlor seats—creates a visual harmony that photographs beautifully. But these pieces were not constructed with contemporary sitting habits, screen time, or lumbar health in mind. Seat depths are often too long, lumbar support is almost nonexistent, and the cushioning has compacted over decades, forcing the pelvis into a posterior tilt that flattens the lumbar curve and stresses discs.

The sophisticated solution is not to banish antique seating, but to treat it more like a visual statement than a daily workstation. Use historic or reproduction chairs for shorter, more formal social sitting—conversation, reading a few pages, enjoying a drink—rather than marathon laptop sessions. When you must work from one, introduce discreet, high-quality lumbar cushions or slim, upholstered wedges in fabrics that echo the room’s palette, so ergonomic support becomes an intentional design choice rather than an obvious medical add-on.

For deep vintage sofas, encourage a “poised lounge” posture rather than a collapsed slouch: place a firm, elegant pillow behind the lower back, and elevate the feet slightly on a low, stable ottoman to reduce strain on the lumbar discs. If you have chronic back issues, consider commissioning a custom, ergonomically informed settee that visually harmonizes with your antique pieces but secretly follows modern seat depth, height, and lumbar contour principles. Think of it as a tailored suit for your spine: period-appropriate in appearance, precision-cut for your body.

3. Narrow Staircases and Uneven Floors: Moving with Architectural Intent

Historic houses often come with tight staircases, slight slants in flooring, or charming irregularities that signal age—and risk. For an irritated lumbar spine, sacroiliac joint dysfunction, or recovering disc injury, these “quirks” can quietly amplify asymmetrical loading with every step. A single habit, like always carrying laundry on the same side up a steep, narrow stair, can, over months, become a meaningful irritant to an already sensitive back.

Instead of fighting these structural realities, treat movement through the home as a kind of daily choreography. Descend narrow stairs with one hand lightly on a rail—if an original banister is too low or too smooth, consider adding a secondary, nearly invisible handrail at an ergonomically appropriate height. When carrying loads, train yourself to alternate sides or use structured baskets with two handles, encouraging a more balanced carry. For those with flare-prone backs, a small, beautifully crafted folding stool or bench placed discreetly near landings or at the top of long staircases can serve as both a design accent and a check-in point when fatigue sets in.

With subtly uneven floors, do not normalize the micro-twists in your gait. If your back is reactive, consider targeted floor corrections in high-use zones—thin, dense underlay beneath rugs, or discreet shimming below large furniture to restore a true level reference. The aim is not to erase every trace of age, but to prevent your spine from absorbing the architectural “wobble” with each step.

4. Clawfoot Tubs and Vintage Vanities: Rewriting Rituals to Protect the Spine

The resurgence of clawfoot tubs, pedestal sinks, and vintage vanities in design magazines and social media feeds has recast bathing and grooming as rituals of luxury. For people with lower back or sacral pain, however, these fixtures can be demanding: low tub rims, wide reaches for taps, and sinks at outdated heights all combine into repetitive forward flexion and twisting—precisely the movements that provoke many lumbar conditions.

If you live with back issues, treat your bathroom like a performance environment that must be meticulously staged. For deep tubs, use a bath board or elevated waterproof stool when necessary, especially if you have difficulty entering and exiting safely. Install a grab bar that blends with existing metal finishes—brushed brass, polished nickel, or aged bronze—so safety becomes part of the design vocabulary. For washing hair, consider using a handheld shower head while kneeling on a dense, supportive bath mat with one knee up and one down, maintaining spinal neutrality instead of folding repeatedly at the waist.

At vintage vanities or pedestal sinks that sit too low, minimize static leaning. Perform tasks that demand longer durations—skincare, makeup, shaving—while seated on an adjustable-height stool with a supportive backrest, positioned so your spine remains tall and your arms rest lightly on the counter. A well-chosen stool, upholstered in a fabric that echoes your towels or window treatment, can look deliberate and luxurious, yet quietly serve as an ergonomic anchor in an otherwise challenging space.

5. Historic Aesthetics, Hybrid Work Realities: Curating a Spine-Safe “Heritage Office”

Perhaps the most striking mismatch between historic homes and contemporary life is the rise of hybrid and remote work. Dining tables that once hosted occasional writing or correspondence are now full-time desk substitutes. Meanwhile, social media continuously celebrates images of sunlit writing desks in front of original sash windows, laden with paper, books, and a slim laptop—visually perfect, physically precarious for a compromised back.

If you live with back concerns, the essential shift is to view your workspace not as a prop within a historic home, but as a carefully curated instrument that happens to reside there. Start by defining one primary workstation that meets your ergonomic standards (correct desk height, supportive chair, adequate monitor elevation), then weave period elements around it rather than forcing your body to conform to a purely aesthetic arrangement. A modern, fully adjustable task chair can be visually softened with a tailored slipcover or custom upholstery in a fabric that resonates with your drapery or wall color, transforming a clinical silhouette into a bespoke piece.

Lighting, too, must be rethought. Relying solely on window light in older homes can push you to hunch closer to the desk as the day darkens. Invest in layered, high-quality lighting—desk lamps with controlled glare, wall sconces at eye level—that allow you to keep your posture stable from morning to night. If you must occasionally work from that irresistible antique writing desk, treat it as a “limited edition” experience: short, defined intervals, mindful posture, and perhaps a standing interlude rather than a daily eight-hour habit.

Conclusion

The renewed fascination with historic homes and timeless craftsmanship is not a superficial trend; it reflects a collective desire for depth, continuity, and meaning in the spaces we inhabit. Yet the spine exists in the present, not the past. It responds to loads, angles, textures, and habits accumulated hour by hour—not to architectural romance.

Living gracefully with back issues in a historic or heritage-inspired environment is less about compromise and more about curation. Every decision—how high a monitor sits beneath a cornice, where a custom lumbar cushion rests on an antique chair, how you descend a narrow stair with intention—becomes an act of quiet design leadership on behalf of your body.

In the most refined homes, comfort is never an afterthought. It is the invisible craftsmanship behind every visible detail. When you allow ergonomics to join architecture, history, and style at the same elevated level, your space stops merely looking timeless—and starts feeling sustainably livable for your spine, right now.

Key Takeaway

The most important thing to remember from this article is that this information can change how you think about Ergonomics.