Our backs are often most vulnerable in the moments that feel least dramatic: the quiet hours at a desk, the long commute, the habitual angle of a phone screen. Ergonomics, when practiced with intention, becomes less about gadgets and more about a refined choreography between body, space, and time. For individuals who already live with back issues, the difference between “tolerable” and “transformational” is often found in the details most people overlook.

Below are five exclusive, under-discussed ergonomic insights designed for those whose backs demand more than generic advice.

1. The “Micro-Posture Portfolio”: Rotating Positions, Not Just Taking Breaks

Conventional guidance recommends standing up every 30–60 minutes. Helpful, yes—but insufficient for a sensitive back. What your spine truly craves is a portfolio of micro-postures across the day, not a binary sit/stand routine.

Instead of returning to the same seated position after each break, deliberately rotate through subtle posture variations:

- Slightly reclined sitting (100–110° hip angle) with lumbar support

- Neutral upright sitting with feet flat and hips just above knee height

- Forward-lean supported sitting (forearms gently rested on the desk)

- Supported standing with one foot elevated on a low footrest and alternated every few minutes

Each of these positions changes load patterns on the discs, facet joints, and surrounding musculature. For a back already under strain, that variation helps prevent any single tissue from absorbing the day’s entire mechanical burden. Think of it as redistributing “stress capital” across the spine.

Crucially, set a subtle cue—a silent phone vibration, a calendar reminder, or a smart watch alert—not to “stand up,” but to change posture intentionally. Over a day, those 20–30 posture shifts are often more protective than a single gym session squeezed in at the end.

2. Visual Ergonomics: The Quiet Architect of Your Spinal Alignment

Most ergonomic advice starts with the chair. A more sophisticated approach begins with your eyes.

When your visual target is too low, too high, or off to one side, your head and neck will adapt—quietly—but your thoracic spine, lumbar spine, and even pelvis will follow. Over time, this visual misalignment becomes a full-spine problem.

Elevate your set-up to a more exacting standard:

- **Primary screen height:** The top line of text should be at or just below eye level. Your gaze should gently fall by about 10–20 degrees, not drop steeply.

- **Viewing distance:** Typically an arm’s length away (about 50–70 cm), but adjusted so you can read comfortably without craning your neck forward.

- **Screen alignment:** Center the most-used screen directly in front of you. A frequently used screen or laptop placed even 10–15 degrees off-center can encourage subtle rotation through the neck and upper back for hours at a time.

- **Secondary devices:** Tablets, phones, and laptops should be elevated when used for more than a few minutes—on a stand, stack of books, or riser—especially if you already have back or neck issues.

For many people with chronic back discomfort, upgrading visual ergonomics reduces not only neck strain but also the unconscious forward collapse of the entire spine. It is often the cleanest, least intrusive change with the highest return.

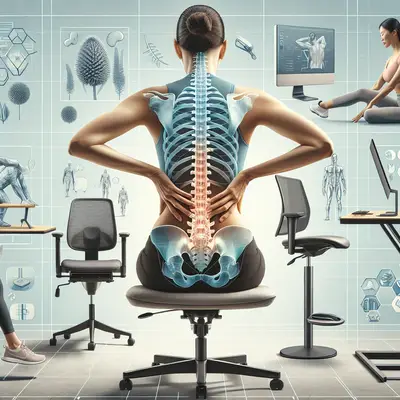

3. Spine-Smart Surfaces: Rethinking the Chair, Cushion, and Floor Relationship

Ergonomics is often framed as “find the perfect chair.” In reality, the interaction between your chair, what you sit on, and what your feet rest against is what decides how your back feels by evening.

Three refined adjustments to consider:

- **Seat depth as a precision tool:** When seated fully back, there should be a 2–3 finger gap between the edge of the seat and the back of your knees. Too deep, and you’ll slouch to reach the backrest; too shallow, and your thighs will be under-supported, transferring tension upwards into the lower back.

- **Firmness with intention:** Overly soft cushions allow the pelvis to sink and tilt backward, flattening your natural lumbar curve. A moderately firm surface that supports the sitting bones (ischial tuberosities) helps maintain a more neutral spinal alignment with less muscular effort.

- **Floor contact as a stabilizer:** Feet should rest fully and firmly on the floor or a stable footrest, with the ankle at roughly 90 degrees. Dangling feet or resting only on the balls of the feet introduces instability that travels up through the knees and hips into the lower back.

For those with existing back problems, a small, high-quality seat wedge or thin lumbar roll—chosen for fit, not trend—can be transformative. The goal is not to force a textbook posture, but to make your “best posture” feel like the easiest option.

4. Load Path Awareness: How Your Hands Quietly Shape Your Spine

Where and how you place your hands determines the path that load takes through your shoulders into your spine. This concept—load path awareness—is rarely discussed, but it is exceptionally relevant if your back is already vulnerable.

Consider these deliberate refinements:

- **Keyboard and mouse as extensions of the shoulder girdle:** Elbows should sit close to the body at about 90–100 degrees, with forearms roughly parallel to the floor. If you have to reach forward or out to the side, your upper back and neck will absorb that effort.

- **Symmetry over perfection:** While perfect symmetry is unrealistic, aim for approximate balance: avoid consistently mousing from a far-out, abducted shoulder position. A compact keyboard, central pointing device, or occasional left/right hand alternation can help.

- **Support points:** Light forearm support on the desk or chair armrests (at matching heights) can decrease the demand on upper trapezius and neck muscles, indirectly easing the load on your thoracic and lumbar regions.

For someone already managing back pain, this is about dignity of effort: how to make each minute of work mechanically “cheaper” for your body. The smaller the muscular demand of each gesture, the more capacity your spine retains for the unexpected stresses of daily life.

5. Temporal Ergonomics: Timing Your Day Around Your Back’s Natural Rhythm

Ergonomics is not only spatial—where things are—but temporal: when you ask your body to perform certain tasks.

Many people with back issues notice distinct “windows” of better or worse function throughout the day. Aligning your schedule with these windows is an elegant, underutilized form of ergonomic intelligence.

Consider:

- **Morning stiffness:** Spinal discs are slightly more hydrated and pressurized early in the day, and many people experience more stiffness in the first 30–60 minutes after waking. Heavy lifting, deep forward bending, or intense sitting during this window can feel disproportionately provocative. When possible, schedule demanding desk work or physical tasks after your back has had time to “warm up” with gentle movement.

- **Cognitive vs physical load pairing:** Reserve your most static, focus-intensive work for your back’s “best” hours and pair your more symptomatic times with tasks that allow micro-movement—phone calls while standing, planning while walking slowly, reading while mildly reclining with support.

- **Evening decompression as a ritual:** Build a brief, non-negotiable decompression practice into the last hour of your working day: gentle supported positions (such as lying on your back with lower legs on a chair), light mobility, or simple breathing drills that reduce muscular guarding. Done consistently, this becomes the ergonomic equivalent of a nightly reset.

By respecting your back’s circadian tendencies, you reduce friction between what your responsibilities require and what your spine can gracefully deliver.

Conclusion

Ergonomics, when viewed through a more refined lens, is less about a single piece of furniture and more about a lifestyle of subtle, intelligent adjustments. For those already living with back issues, the luxury is not in extravagant equipment, but in precision: the exact angle of your screen, the firmness of your seat, the path of your hands, and the timing of your tasks.

When you orchestrate these details with intention, your environment stops working against your back and begins quietly working for it. Over days and weeks, those nearly invisible shifts can translate into something profoundly tangible: a back that feels better supported, less reactive, and more capable of carrying the weight of a demanding life.

Sources

- [National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH): Ergonomics and Musculoskeletal Disorders](https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/ergonomics/) - Overview of ergonomic principles, risk factors, and workplace recommendations

- [Mayo Clinic – Office Ergonomics: Your How-To Guide](https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/adult-health/in-depth/office-ergonomics/art-20046169) - Practical guidance on workstation setup for reduced back and neck strain

- [Harvard Health Publishing – The Health Hazards of Sitting](https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/the-health-hazards-of-sitting-201201111110) - Discussion of prolonged sitting, spinal load, and the benefits of movement variation

- [Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) – Computer Workstations eTool](https://www.osha.gov/etools/computer-workstations) - Detailed recommendations on monitor, chair, keyboard, and input device positioning

- [Cleveland Clinic – Low Back Pain: Prevention and Treatment](https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/4635-low-back-pain) - Clinical perspective on back pain contributors, including posture and ergonomics

Key Takeaway

The most important thing to remember from this article is that this information can change how you think about Ergonomics.