For many people, “ergonomics” still conjures images of stiff office chairs and chunky keyboard trays. But for those who live with back issues, true ergonomics is far more intimate: it is the quiet choreography of how you move, reach, rest, and restore your spine from morning to night.

When ergonomics is done well, your space begins to feel like it was designed for your body, not against it. Chairs become supportive allies instead of tolerated necessities; everyday tasks feel fluid instead of fatiguing. Below are five elevated, often-overlooked ergonomic shifts that move beyond generic advice—and into the realm of truly refined back care.

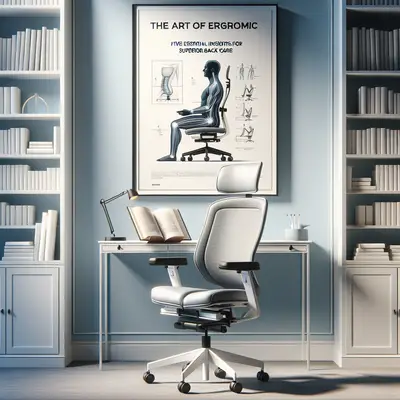

1. Treat Your Chair as a Tailored Garment, Not a Single Purchase

Most chairs are bought like shoes in the wrong size: chosen quickly, worn daily, and quietly resented. For someone with back concerns, your chair should be more like a tailored garment—customized, adjusted, and periodically “refitted” as your body and habits evolve. Begin with the basics: your hips should be slightly higher than your knees, allowing your pelvis to tilt gently forward and preserve the natural curve of your lower spine. From there, refine the fit. If the lumbar support presses uncomfortably, it is not “supporting”—it is pushing; adjust it or add a slim cushion that precisely matches the hollow of your lower back.

Pay attention to seat depth: if the chair cuts into the back of your knees, your circulation and posture will both suffer. You should be able to slide two to three fingers between the seat edge and your calves. Finally, accept that one static position—no matter how perfectly set up—cannot accommodate a living spine. Revisit your chair adjustments every few months the way you might take in or let out a favorite blazer. As your core strength, flexibility, and pain patterns change, your “fit” should follow.

2. Design a “Reach Radius” That Protects Your Spine From Subtle Overwork

Most back strain in a workspace doesn’t come from one dramatic twist or bend—it comes from hundreds of tiny, repeated reaches that slowly exhaust the supporting muscles along your spine. Consider the objects you touch most in a day: your phone, mouse, notepad, water glass, frequently used documents. If any of them require you to lean or twist repeatedly, your back is quietly paying for that layout.

Create what can be thought of as a “neutral reach radius”: a semicircle from your midline where both arms can access essentials with elbows near your body and shoulders relaxed. This is not merely about convenience—it is about load distribution. When elbows stay close to your torso, your spine is supported by a more stable foundation, reducing the micro-strain that accumulates as fatigue or aching by late afternoon. For those with existing back issues, bring high-frequency tools closer than you think you need: think fingertip distance, not stretching distance.

Extend this philosophy beyond the desk. In the kitchen, store heavier items (cast-iron pans, large mixers, bulk containers) between hip and chest height, ideally within one or two steps of your main work area. In the wardrobe, place everyday shoes and frequently worn clothing where you can access them without repeated bending or overhead reaching. Elegance in ergonomics is efficiency—your spine should not need to work heroically to accomplish the ordinary.

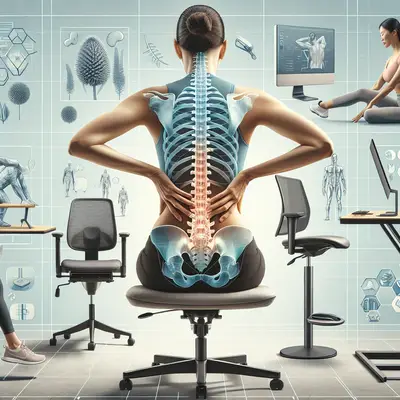

3. Curate a “Posture Palette” Instead of Chasing One Perfect Position

Standard ergonomic advice often implies there is a single “ideal posture” to maintain all day. Anyone with a sensitive back knows this is a myth. A static spine—even in flawless alignment—will eventually complain. Instead, curate what might be called a “posture palette”: a small collection of intentional positions you cycle through every 30–60 minutes.

For example, you might work part of the hour in a well-supported seated posture, part in a slightly reclined position with your back fully supported and screen elevated, and part at a standing desk with one foot slightly elevated on a small footrest to ease your lower back. Each posture should respect the natural curves of your spine, keep your head balanced over your shoulders, and avoid compressing any one segment for too long. Think of your day as a sequence of elegant, deliberate adjustments rather than a battle to “hold” one rigid stance.

For those with significant back issues, integrate micro-movements into each posture: gentle pelvic tilts, subtle shoulder rolls, small weight shifts from one leg to the other while standing. These almost invisible motions help circulate nutrients to the discs, prevent stiffening of the facet joints, and keep supporting muscles active without excessive strain. A refined ergonomic setup is not a museum display; it is a living environment that quietly invites movement.

4. Make the Floor a Therapeutic Surface, Not Just Something You Stand On

We often obsess over chairs and desks while ignoring the foundation under everything: the floor. Yet for people with back pain, what you stand and walk on across the day can deeply influence how your spine feels by night. Hard, unyielding floors—especially when combined with unsupportive footwear—transfer shock directly up the kinetic chain into your knees, hips, and lower back.

If you stand for extended periods, invest in a high-quality anti-fatigue mat with both support and subtle “give,” placed wherever you spend the most time on your feet: at a standing desk, in the kitchen at your primary prep area, or at a workbench. The best mats guide your body into tiny balancing adjustments that keep your leg and core muscles engaged without exhausting them, lightening the load on passive spinal structures. Pair this with thoughtfully chosen footwear: firm in the midfoot, cushioned under the heel, and stable enough to prevent excessive rolling inward or outward of your ankles.

Consider, too, how you use the floor for intentional rest. Short, structured breaks lying on a firm, carpeted or lightly padded surface—knees bent, feet flat, a small support under your head—can temporarily “decompress” the spine. This is not simply relaxation; it is an ergonomic reset. Even two to five minutes in this position can help restore neutral alignment after hours of sitting or standing. The most sophisticated back-care routines often include these quiet, restorative intervals that require nothing more than intentional contact with the ground.

5. Integrate “Transition Ergonomics” Into Every Change of Position

Most ergonomic conversations focus on where you are—sitting, standing, lying—rather than how you get there. Yet for those with back concerns, transitions are often when discomfort or injury happens: getting out of bed, rising from a low sofa, exiting a car, leaning into the backseat, or picking something off the floor “just this once.”

Begin to treat every transition as a small movement ritual that protects your spine. When rising from a chair, bring your feet slightly back under you, hinge at the hips rather than rounding your back, let your chest move forward over your knees, and then press through your legs as your spine follows in one smooth line. When getting out of bed, roll onto your side first, slide your legs off the edge, and push yourself up with your arms as your feet find the floor—rather than jackknifing directly from your back.

Adopt thoughtful mechanics for lifting even modest loads: keep the object close to your body, hinge at the hips with a neutral spine, and share the work between your legs and core instead of asking your lower back to “pull” the weight. The goal is not to live in fear of movement, but to cultivate such consistent, graceful habits that they become automatic. True ergonomic luxury is not just a beautiful chair or adjustable desk; it is the quiet confidence that every transition in your day respects your spine.

Conclusion

Elevated ergonomics is not about surrounding yourself with expensive equipment; it is about curating an environment—and a set of habits—that allow your spine to move, rest, and work with dignity. For those managing back issues, the details matter: the angle of your hips, the reach of your arm, the firmness of the floor, the path you take from lying to standing.

When you refine these small interactions with your world, your day begins to feel less like a series of physical negotiations and more like a thoughtfully designed experience. Your back, in turn, is no longer an obstacle to be managed, but a central asset to be preserved—quietly supported by an ergonomic life that is as intentional as it is sophisticated.

Key Takeaway

The most important thing to remember from this article is that this information can change how you think about Ergonomics.