Back pain has a way of revealing every flaw in our environment. The chair that once felt “fine,” the laptop that seemed “good enough,” the flight you could previously endure—suddenly all feel misaligned with your body’s new reality. For those navigating back issues, ergonomics is no longer a generic workplace suggestion; it becomes a form of precision self-care, where small adjustments accumulate into meaningful relief.

This is ergonomics not as a buzzword, but as a quiet, deliberate geometry of comfort—where every surface, angle, and gesture either protects your spine or slowly withdraws from it.

Ergonomics as Spatial Design, Not Just Desk Setup

Traditional ergonomic advice fixates on desk height and chair settings. Useful, yes—but incomplete. When your back is vulnerable, the real question becomes: how does your entire space either support or strain your spine?

Begin by mapping the “reach zones” around you. Objects you use hourly—phone, water, notebook, mouse—should sit within a relaxed arm’s reach, avoiding twisting or forward bending. Frequently accessed items stored low (under desks, bottom drawers, floor-level shelves) create small but repetitive spinal demands that accumulate across the day.

Lighting is another underestimated stressor. Poor lighting invites neck craning and micro-forward head posture as you lean into the screen or documents. Thoughtfully placed task lighting can reduce this unconscious lean, preserving a neutral spine without mental effort.

For those with back issues, the most refined ergonomic spaces feel almost frictionless: minimal reaching, no need to “lean in” to see, and no repeated contortions just to access what you use most.

The Spine-Informed Chair: Beyond “Good Lumbar Support”

“Lumbar support” has become a marketing phrase, but not all support is created equal—and for an irritated spine, the distinction matters.

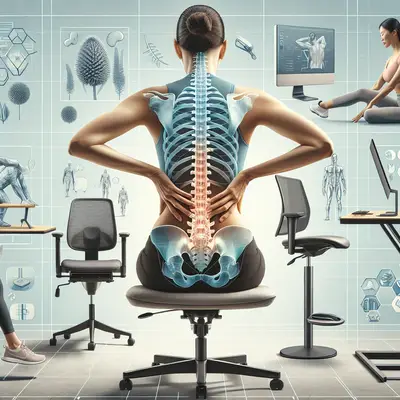

A spine-informed chair considers three subtleties:

**Dynamic, not rigid, support**

Your lumbar region should feel gently held, not braced. Overly firm support can lock you into a single posture, which may aggravate certain back conditions. The ideal is a backrest that follows you subtly as you shift, supporting your natural curve without forcing one identical position.

**Seat depth as a precision setting**

If the seat is too deep, you’ll slide forward, losing back contact and slumping. Too shallow, and your thighs feel partially supported, restricting comfort over time. Aim for a small gap—about two to three fingers—between the front of the seat and the back of your knees, allowing full back contact without pressure at the knees.

**Micro-adjustments as a daily ritual**

Instead of setting your chair once and forgetting it, treat adjustments as part of your daily rhythm. Raise the chair slightly when typing, lower it a touch for reading printed material, recline a few degrees during calls. These subtle shifts distribute load across different structures in your spine and hips, reducing the cumulative burden of static sitting.

The goal is less about owning “the perfect chair” and more about cultivating a relationship with your chair—one where you remain an active participant rather than a passive occupant.

The Laptop Paradox: Mobility vs. Mechanical Cost

Laptops are marvels of mobility and disasters of alignment. The screen is attached to the keyboard, forcing a compromise: your eyes or your spine.

For someone managing back issues, this compromise becomes costly. A few refined strategies elevate laptop use from tolerable to deliberately spine-friendly:

- **Detach the typing from the viewing.**

A slim external keyboard and mouse allow you to raise the laptop to eye level while keeping your shoulders relaxed and elbows near 90 degrees. This single change often transforms posture from collapsed to composed.

- **Treat couch and bed use as short, intentional intervals.**

Reclining with a laptop propped on your thighs often forces the neck into sustained flexion and the mid-back into rounding. If you must work from the sofa or bed, use firm pillows behind your back, elevate the screen on a pillow or stand, and limit sessions to brief periods—then return to a more structured setup.

- **Align work sessions with your back’s “tolerance windows.”**

Most people with back issues notice times of day when their spine is more forgiving. Reserve laptop-heavy tasks for these windows, and use more upright or paper-based work when your back begins to fatigue.

The refined approach is not to abandon the laptop, but to strip away the unconscious compromises it imposes—and rebuild your setup with your spine as the design brief.

The Art of Transition: Protecting Your Back Between Postures

For many, pain flares not while sitting or standing, but in transition: getting out of the car, rising from a low chair, bending to pick something up. These in-between moments are where ergonomics becomes choreography—how you move through your environment, not just how you inhabit it.

A few transition-focused refinements:

- **From sit to stand:** Scoot to the front of the chair, place your feet slightly behind your knees, lean forward with a straight (not rounded) back, and press through your legs. Let your hips and thighs do the lifting, not your spine.

- **From lying to sitting:** Roll to your side first, bring your legs off the bed as a unit, and press up with your arm. Avoid jackknifing straight up from your back, which compresses the spine under load.

- **Reaching low:** Rather than bending from the waist, hinge at the hips with a slight knee bend, keeping your spine relatively neutral. For very low items, consider a “golfer’s lift”: hold onto a stable surface with one hand while reaching one leg back as you lower your torso, keeping the spine aligned.

Cultivating graceful, deliberate transitions is an often overlooked ergonomic upgrade. You are not just optimizing the surfaces you use—you are refining the way your body meets them.

Curating Recovery Micro-Moments Into Your Day

Many think of rest as something that happens in hours: a good night’s sleep, an afternoon lying down. For a sensitive back, recovery is also built in minutes—well-placed micro-moments that re-balance what prolonged sitting, standing, or travel has taken.

Consider integrating spinal “intermissions” into your day:

- **Neutral resets:** Lying on your back with knees bent and feet flat on the floor (or on a sofa) can gently unload the spine. Even two to five minutes between meetings can shift how your back feels by evening.

- **Axis-awareness breaks:** Stand tall, imagine a lengthening from the crown of your head through your tailbone, and allow your shoulders to soften down. This subtle, vertical “reset” reminds your body of alignment without effortful posture “holding.”

- **Rotation-free pauses during flare-ups:** When your back is particularly irritated, avoid deep twists. Use your micro-breaks to focus on neutral or gentle extension positions that feel safe, rather than chasing dramatic stretches.

These moments are not indulgences; they are precision maintenance. Over a week, a month, a quarter, they can be the difference between a background hum of discomfort and a spine that feels steadily more supported.

Conclusion

Elegance in ergonomics is not about acquiring premium objects; it is about cultivating premium attention. How high your screen sits, how your knees relate to your hips, how often you change angle, how you rise from a chair—all of it quietly shapes your spine’s story.

For those living with back issues, this story is written in nuances: centimeters of screen height, degrees of recline, minutes between movement, the choreography of getting in and out of a car. A sophisticated ergonomic approach does not promise a life without discomfort, but it does offer something powerful: a sense that your environment is finally collaborating with your body, not working against it.

In that collaboration lies a quieter spine, a more composed day, and a standard of comfort that feels not like a luxury, but like a well-considered baseline.

Sources

- [National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke – Low Back Pain Fact Sheet](https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/low-back-pain) – Overview of causes, risk factors, and management options for low back pain.

- [Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) – Computer Workstations eTool](https://www.osha.gov/etools/computer-workstations) – Detailed guidance on configuring workstations, including seating, monitor placement, and input devices.

- [Mayo Clinic – Office Ergonomics: Your How-To Guide](https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/adult-health/in-depth/office-ergonomics/art-20046169) – Practical recommendations for workstation setup and posture adjustments.

- [Harvard Health Publishing – How to Sit Correctly](https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/how-to-sit-correctly) – Evidence-informed advice on sitting posture and spine-friendly positioning.

- [Cleveland Clinic – Back Pain Basics](https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/10308-back-pain) – Comprehensive explanation of back pain types, contributing factors, and prevention strategies.

Key Takeaway

The most important thing to remember from this article is that this information can change how you think about Ergonomics.