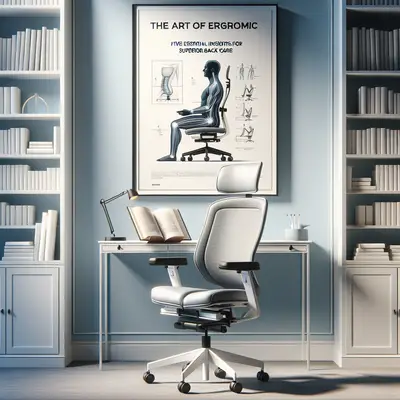

In a world that expects you to think sharply and move seamlessly, the way you sit, stand, and work becomes an underappreciated form of craftsmanship. Ergonomics is no longer just about “not slouching”; it is about creating a working environment that respects the complexity of your spine, your nervous system, and your capacity for sustained performance. For those already negotiating back discomfort, small design decisions can distinguish a merely tolerable day from a genuinely sustainable one.

This is ergonomics as quiet mastery: discreet adjustments, deliberate choices, and an environment calibrated to let your back work less while your mind does more.

Ergonomics as Load Management, Not Posture Policing

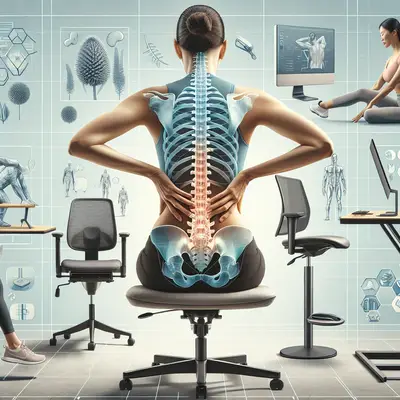

Most conversations about ergonomics begin and end with posture, as if holding a “perfect” position were the pinnacle of spinal health. In reality, the spine is an adaptable, living structure that thrives on varied, well-managed load—not rigid stillness.

Instead of chasing an ideal pose, think in terms of load distribution. Your chair, desk, keyboard, and screen all exist to share the mechanical burden your back would otherwise absorb alone. A seat pan that supports the thighs but doesn’t press behind the knees, a slightly reclined backrest (around 100–110 degrees) paired with lumbar support that meets—not pokes—the natural curve of your lower back, and armrests positioned so the shoulders rest rather than hover: each is a strategy to diffuse load.

For those with existing back issues, this distinction is crucial. A stiff, “perfect” posture can increase compressive forces on already-irritated structures. A thoughtfully adjusted environment, by contrast, allows gentle micro-movements, small shifts in weight, and subtle recline—each movement a pressure reset for discs, joints, and muscles that are already under negotiation.

Exclusive Insight #1: Treat your chair and desk as partners in load-sharing, not devices that force you into a single ideal posture.

The Micro-Break as a High-Performance Habit

The body is remarkably forgiving for the first thirty minutes of sitting; beyond that, even an excellent setup begins to fail you if you remain motionless. Long, uninterrupted sitting silently accumulates stress in the spine, hips, and surrounding musculature.

Micro-breaks—30 to 90 seconds of purposeful movement every 30 to 45 minutes—act as a reset button for your back. This does not require leaving your workflow in disarray. Stand and gently shift your weight from one leg to the other, lightly march in place, roll your shoulders, or perform soft hip circles. These micro-breaks reduce static load, support circulation, and encourage the intervertebral discs to rehydrate and redistribute internal pressure.

For those dealing with persistent back discomfort, micro-breaks are less about “exercise” and more about precision load relief. Rather than waiting for pain to spike, you preempt it with disciplined, near-invisible ritual that preserves both spine and schedule.

Exclusive Insight #2: Schedule micro-breaks as non‑negotiable performance tools, not optional wellness extras.

Calibrating Visual Ergonomics to Protect Your Spine

Back strain often begins with the eyes. When screens are too low, too far, too bright, or too cluttered, you instinctively crane your neck, lean forward, or twist subtly to gain clarity. Over hours and months, these micro-compromises compound into neck and upper-back fatigue, tension headaches, and mid-spine stiffness.

An ergonomically refined workstation begins with visual ease. Your primary monitor should sit directly in front of you, about an arm’s length away, with the top of the screen roughly at or slightly below eye level. If you wear progressive lenses, subtly lowering the monitor can help you avoid tilting your head back. Secondary screens should be arranged so that your torso, not just your neck, rotates to view them, minimizing asymmetrical strain.

Lighting deserves equal consideration. Excessive glare, harsh overhead lighting, or sharp contrast between screen and surroundings can quietly coax you into forward head posture as your body chases clarity. Soft, indirect lighting, anti-glare screens or settings, and appropriately adjusted brightness create a visual environment where your neck and upper back can remain naturally aligned.

Exclusive Insight #3: Design visual ease first—your neck and upper back will follow.

The Subtle Power of Surface Height and Reach

Many ergonomic frustrations are not dramatic; they are barely perceptible misalignments repeated thousands of times a day. Desk height and reach zones are two of the most underrated yet transformative elements for anyone with back sensitivities.

Your desk surface should allow your forearms to rest approximately parallel to the floor when your shoulders are relaxed and your elbows bent near 90 degrees. If the desk is too high, the shoulders creep upward and the neck and upper back tighten. Too low, and you lean forward, increasing lumbar and cervical strain. For those who cannot change desk height, an adjustable chair combined with a footrest can restore balance, allowing proper arm position without compromising lower-body support.

Equally important is the primary reach zone: the space within which your elbows remain close to your body while you access frequently used items. Keyboards, pointing devices, and primary input tools should live here. Repeatedly reaching forward or twisting for a mouse placed too far away seems inconsequential in the moment, yet for a sensitized spine it can be the difference between stability and end-of-day fatigue.

Exclusive Insight #4: Prioritize comfortable surface height and a close, symmetrical reach zone to protect a sensitized spine from constant micro-strain.

Standing, Moving, and the Myth of the “Perfect” Chair

A premium ergonomic setup is not defined by a single extraordinary chair; it is defined by how fluidly you transition between positions over the course of a day. For those managing back issues, variety—executed intelligently—is often more valuable than any single seating solution.

If you use a sit–stand desk, think in terms of rotation, not replacement. Standing for endless hours simply substitutes one static posture for another. Alternate between sitting and standing every 30 to 60 minutes, using transitions as opportunities to reset your alignment. When standing, keep your weight balanced over both feet, consider a small footrest or foot rail to occasionally elevate one foot, and avoid locking your knees.

Chairs remain essential. A well-designed, adjustable chair supports recline, allows slight rocking or dynamic backrest movement, and invites small shifts of position. For some people with low-back sensitivity, a modest recline with lumbar support can feel significantly more sustainable than full upright sitting, as it gently reduces disc pressure. The most refined solution is not a single “miracle” position, but an ecosystem that privileges controlled movement over prolonged stillness.

Exclusive Insight #5: Think in terms of a posture portfolio—a curated rotation of supported positions—rather than searching for one perfect chair or stance.

Conclusion

Ergonomics, at its most sophisticated, is less about furniture and more about discernment. It is the quiet, ongoing act of choosing arrangements that respect your spine’s need for variety, balanced load, visual ease, and subtle movement. For those already navigating back issues, this is not indulgence; it is structural self-respect.

By treating your environment as an extension of your back care—not an afterthought—you create conditions in which your spine can work less chaotically while you live and work more intentionally. The ultimate luxury is not an ornate chair or an avant‑garde desk; it is a day in which your back remains largely unremarkable, free to support you without demanding the spotlight.

Sources

- [National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke – Low Back Pain Fact Sheet](https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/low-back-pain) - Overview of causes, risk factors, and management strategies for low back pain

- [Mayo Clinic – Office Ergonomics: Your How-To Guide](https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/adult-health/in-depth/office-ergonomics/art-20046169) - Practical guidelines for arranging desk, chair, and equipment to protect the back

- [Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) – Computer Workstations eTool](https://www.osha.gov/etools/computer-workstations) - Detailed best practices for workstation setup, including chair, monitor, keyboard, and lighting

- [Harvard Health Publishing – Prolonged Sitting and Back Pain](https://www.health.harvard.edu/pain/prolonged-sitting-and-back-pain) - Discussion of how sitting affects the spine and why movement breaks matter

- [Cleveland Clinic – Standing Desks: How They Help You Stay Healthy](https://health.clevelandclinic.org/standing-desks-benefits) - Evidence-based insights on sit–stand workstations and how to use them effectively

Key Takeaway

The most important thing to remember from this article is that this information can change how you think about Ergonomics.