Back pain has a way of intruding on even the most carefully curated life. It is the small, persistent discomforts—the dull ache at 4 p.m., the stiffness during a flight, the tension after a working dinner—that quietly erode your focus and your sense of ease. Ergonomics, when done well, is not about gadgets or gimmicks. It is about orchestrating your environment so your spine can be both supported and unburdened, allowing you to move through demanding days with quiet confidence.

This is a more elevated approach to ergonomics: subtle adjustments, tailored awareness, and five exclusive insights that matter profoundly when your back has already made its presence known.

The Hidden Geometry of Your Day

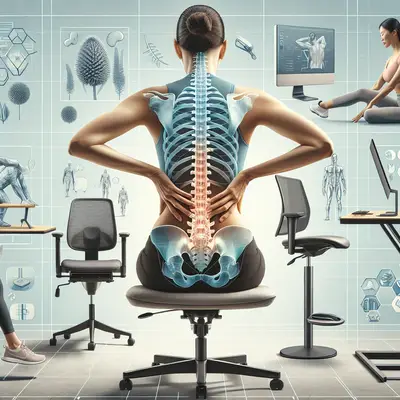

For those living with back issues, the most important ergonomic variable is not your chair or your desk—it is your daily movement geometry. Think of your day not as “sitting vs. standing,” but as a continuous choreography of angles, durations, and transitions.

Spinal structures—discs, ligaments, small stabilizing muscles—respond poorly to being held at a single angle for prolonged periods, even if that position looks “perfect.” A neutral spine is essential, but a neutral spine that never moves is still under stress. The healthiest back typically experiences gentle variation: 90–110° hip angles, small shifts in weight-bearing, subtle alternation between sitting, leaning, and standing.

When you map your day in terms of positions rather than tasks, patterns emerge: the two-hour commute with no lumbar support, the laptop lunches on a low coffee table, the late-night tablet reading in bed with the neck flexed forward. These are not dramatic errors; they are small, cumulative insults. Ergonomic refinement begins by identifying and smoothing these geometric “pressure points” in your schedule.

A useful lens: every 30–45 minutes, your spine should experience a change in angle, support, or load. That principle is far more powerful than any single “perfect” chair.

Insight 1: Curate Height, Not Just Posture

Most ergonomic advice centers on posture—“sit upright,” “keep your shoulders back.” For a back that has already endured strain, a more sophisticated focus is height: the relative height of surfaces, screens, and supports in relation to your body.

When your surfaces are too low, you fold forward, compressing the front of your spine, straining the neck, and overworking the upper back. When they are too high, your shoulders lift subtly toward your ears, creating tension that often manifests as a dull, radiating ache into the shoulder blades. Both scenarios can aggravate existing spinal issues, particularly in the cervical and thoracic regions.

Refined ergonomic practice treats height as a customized measurement, not a generic standard. Your desk height should allow your elbows to rest just below or at a 90° angle, your forearms supported lightly, and your shoulders entirely un-elevated. Your screen should meet your gaze, not invite a downward tilt of the head. Even your frequently used objects—phone, notebook, glass of water—should live within easy reach, so you are not repeatedly twisting or leaning across your desk.

This height curation extends beyond the office. Kitchen counters where you prep meals, the bathroom sink where you lean over to wash your face, the home bar where you stand to pour a drink—each is an opportunity to reduce small but repetitive spinal stresses. Over time, these quiet refinements can matter more than any single “ergonomic” purchase.

Insight 2: Design Transitions as Carefully as Workstations

Ergonomic design typically stops at the workstation. Yet for many people with back issues, the most provocative moments are transitional: getting out of the car, rising from a low sofa, lifting a carry-on into an overhead bin, turning in bed.

These micro-movements are where compromised discs are pinched, irritated nerves are provoked, and sensitized joints are reminded of their limitations. A sophisticated ergonomics strategy therefore includes “transition design”: deliberately smoothing the way you move between positions and environments.

This may mean:

- Selecting chairs and sofas with enough seat height and firmness that you can rise without a deep forward bend or momentum-driven “heave.”

- Positioning your car seat so the angle of the backrest, seat depth, and steering wheel allow you to exit with a relatively neutral spine, not twisted and flexed simultaneously.

- Organizing your luggage and tote bags so heavier items are closer to your body, reducing leverage on the lower back when lifting or rotating.

- Using stable touchpoints—armrests, countertops, headboards—intentionally, so transitions are supported, not improvised.

None of this is dramatic. That is precisely the point. With a sensitized back, the cumulative load of “harsh” transitions is often what keeps pain lingering. When you design transitions, you transform the most vulnerable moments into predictable, supported movements.

Insight 3: Treat Your Chair as an Instrument, Not a Throne

Premium chairs are marketed as if they are thrones—set them up once and be done. In reality, the best chair is more like a finely tuned instrument that you adjust throughout the day to match the piece you are playing.

For someone with back issues, the static “ergonomic setup” is a trap. Your spine has fluctuating needs: more lumbar support during long focus sessions, slightly reclined angles when fatigue creeps in, more upright support when typing intensely, more open hip angles after sitting in traffic.

Instead of locking your chair into one ideal, consider three to four “presets” you use consciously:

- A slightly reclined, well-supported position for deep thinking or reading.

- A more upright, active posture for typing or video calls.

- A more open, almost lounge-like angle—still supported—for recovery intervals.

- A short standing interval with gentle foot movement to offload the spine.

Leaning into the adjustability of your chair—seat pan depth, lumbar firmness, backrest tension, armrest height—is not indulgent; it is spinal risk management. Frequent micro-adjustments vary the load on your discs and joints, reducing the strain that comes from any single, unchanging posture, even if that posture is technically “correct.”

Insight 4: The Subtle Tax of Travel and Social Spaces

Back-conscious ergonomics often collapses at the airport lounge, in the rideshare, or at the restaurant table. Yet these “informal” environments can be particularly punishing when your spine is already vulnerable.

Travel seating frequently combines three stressors: prolonged sitting, restricted movement, and compromised alignment. Eating or working with a laptop in transit often adds forward flexion and rotation—an unhelpful formula for a back prone to irritation. In social settings, low, deep sofas and stylish but unsupportive chairs invite slouching, posterior pelvic tilt, and prolonged strain on lumbar discs and ligaments.

An elevated approach is to anticipate and gently redesign these environments where possible:

- In flights or trains, use compact lumbar supports or a rolled scarf at the small of the back, and angle the seatback to avoid aggressive flexion or extension of the spine.

- At restaurants, subtly adjust your distance from the table so you do not reach forward for hours; if chairs are too low or deep, sit toward the front of the seat with feet flat and spine supported away from the backrest slump.

- In cars, align the headrest with the back of your head (not your neck) to discourage forward head posture and adjust seat tilt to avoid a “bucket” position that rolls the pelvis backward.

- In lounges or living rooms, do not hesitate to add a cushion behind the lower back or choose a firmer, more upright seat if available.

This is ergonomics as quiet self-advocacy: not drawing attention, but never surrendering your back to design choices made purely for aesthetics or space efficiency.

Insight 5: Refined Ergonomics Extends Beyond Furniture

True ergonomic sophistication recognizes that the body is not a collection of parts but an integrated system—muscle tone, breathing patterns, stress levels, sleep quality, and recovery all influence how your spine experiences the environments you design.

A workstation can be flawlessly arranged, but if your paraspinal muscles are constantly clenched from stress, or if you sleep in a twisted, unsupported posture for six hours each night, your back will remain unsettled. Prolonged sympathetic arousal (the “fight-or-flight” state) can heighten pain sensitivity, making minor ergonomic flaws feel severe.

Refined ergonomic care therefore includes:

- Lighting that reduces eye strain and discourages forward head posture.

- A predictable rhythm of short movement breaks—standing, gentle extensions, or brief walks—to restore circulation to spinal tissues.

- Sleep surfaces and pillows that keep your neck and lumbar region in neutral, avoiding extremes of flexion or extension.

- Stress management practices—breathing, brief pauses between tasks, or even mindful transitions—that soften unconscious bracing in the neck, shoulders, and lower back.

In this sense, ergonomics is not simply about props and positions; it is the architecture of how your body meets the demands of your day. When you address the broader system, each carefully chosen chair, desk, or support becomes markedly more effective.

Conclusion

For a discerning spine, ergonomics is not a collection of gadgets or a one-time office makeover. It is an ongoing, intelligent dialogue between your body and the environments you inhabit—at work, in transit, and at home.

By curating height rather than obsessing over a single posture, designing transitions as thoughtfully as workstations, treating your chair as an adjustable instrument, managing the subtle tax of travel and social spaces, and extending ergonomics beyond furniture into movement, sleep, and stress, you move from coping to cultivating.

The result is not merely less pain, but a more composed, capable presence in everything you do—a life in which your back quietly supports your ambitions instead of limiting them.

Sources

- [National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke – Low Back Pain Fact Sheet](https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/low-back-pain) - Overview of causes, risk factors, and management of low back pain

- [National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) – Ergonomics and Musculoskeletal Disorders](https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/ergonomics/default.html) - Evidence-based guidance on workplace ergonomics and spine-related risks

- [Mayo Clinic – Office Ergonomics: Your How-to Guide](https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/adult-health/in-depth/office-ergonomics/art-20046169) - Practical recommendations for refining desk and chair setup

- [Harvard Health Publishing – Prolonged Sitting and Back Pain](https://www.health.harvard.edu/pain/prolonged-sitting-and-back-pain) - Discussion of sitting, spinal load, and posture-related back issues

- [Cleveland Clinic – Good Posture for a Healthy Back](https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/4485-back-health-and-posture) - Insights on posture, alignment, and their impact on spine health

Key Takeaway

The most important thing to remember from this article is that this information can change how you think about Ergonomics.